The first time I heard Gillian Ayres’ name, I didn't know who she was. But by the time I encountered her work, her name was no longer unfamiliar. I had planned to see her when I visited England, but my trip was rushed (and she didn’t live in London) — so we were unable to meet. But I understood her much better, and also heard a lot more about her, when I was able to see her paintings in London. It all led me to think more deeply about art, and especially about the meaning of painting.

In the history of modern British art that is usually available to us in China, we often learn about, or are told about, Henry Moore, Richard Hamilton, Francis Bacon, Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, and Marc Quinn. It is as if these figures constitute contemporary British art — and that the “narrative” of British art is configured around these artists. Our understanding of British contemporary art seems to be fixed in this way, as if this were all of British contemporary art. In a similar way, Chinese contemporary art has been choreographed around a few familiar names, too. But in both British and Chinese art, is the story told around a few familiar artists really the whole story?

Gillian Ayres’ Sailing Off the Edge is an exhibition that will allow us, in China, to discover an artist and some wider truths — as with the John McLean exhibition Like Singing and Dancing, which was held at CAFA last year. Like Gillian Ayres, the name of John McLean was unfamiliar to me when I first heard it. But after I visited him in his London home and in his studio in southeast London, he was no longer a stranger, and I began to have a new sense of what counts as British art. This new understanding was confirmed and intensified when I encountered the work of Gillian Ayres.

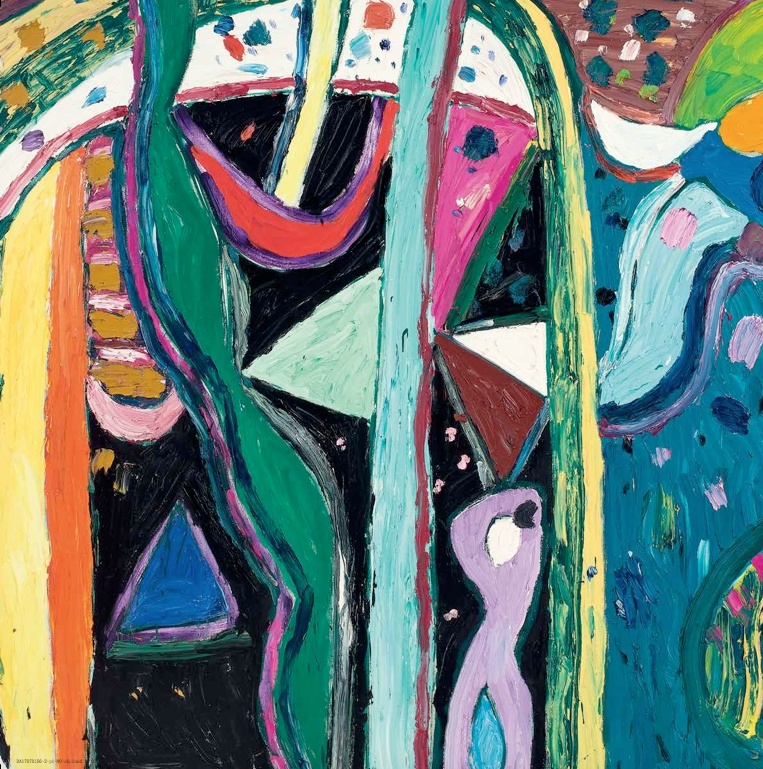

Untitled (Rome Series II) (detail), 1997, Oil on canvas, 243.8 × 213.4 cm

Untitled (Rome Series II) (detail), 1997, Oil on canvas, 243.8 × 213.4 cm

In one sense I could compare her work to work by Chinese artists. In another sense it allowed me to see how partial is the usual account of the development of abstract art in the West that we are told in China. Gillian Ayres has worked in abstraction all her life, but you won’t see her name and work in many of the art history textbooks we read. For us, abstract art is almost always linked to figures such as Kandinsky, Mondrian and Pollock. Some even say that abstract art is “complete” — and that it is no longer in the vanguard of our times, as it once was. Is this the case? In Chinese art history, landscape painting appears generation after generation; and if we discuss the art of China through changes in subject matter or medium, then we won’t really see the changes that have actually taken place in the history of art. After all, the same mountains (in shan shui paintings) were reproduced by countless classical artists, and the same brushwork techniques were used by innumerable painters. It can seem as if time has stood still. However, if we look at life itself we don’t see it that way. The sun may rise every day, but it is our experience of life that matters. What marks painters is that their most profound experience of life is to be found in the act of making art. It is that experience that is at the heart of Gillian Ayres’ paintings.

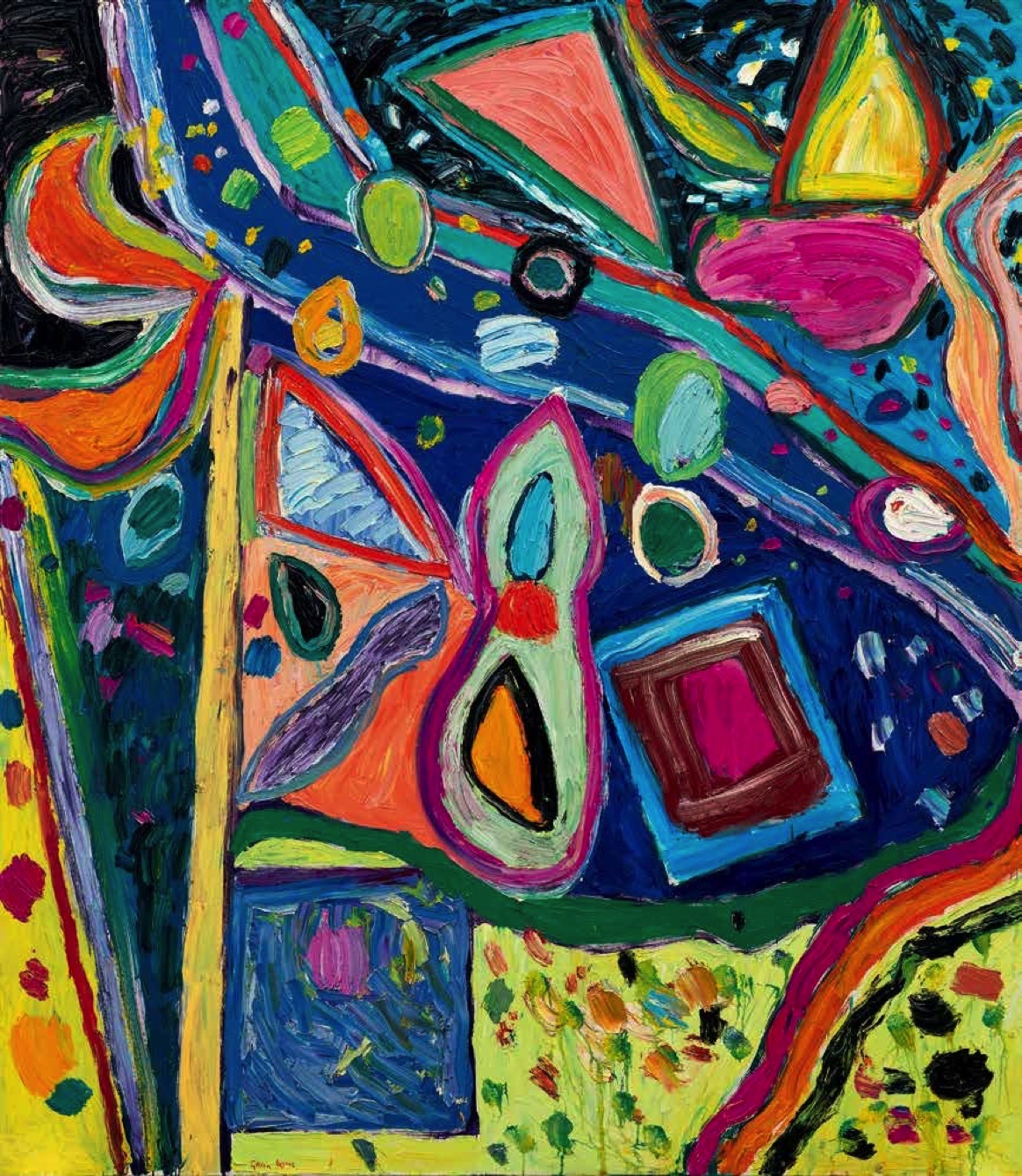

Untitled (Rome Series I), 1997, Oil on canvas, 243.8 × 213.4 cm

When she uses her brush to paint freely on a canvas, we feel her vitality and passion; she makes her canvas alive, filling it with her weight and heat. Her brushwork and use of colour are bold and vigorous, creating unrestrained forms. The key to her work is its grandeur and heroism. The principle behind that grandeur and heroism can be found in a story. In Cornwall, where she lives and paints, her studio is small, so her large paintings cannot be moved out of the house through the door. Her reaction was to make a large slit in the wall so that the large paintings could be removed. When I saw the photograph of the house, a knowing smile spread across my face, and I understood Gillian Ayres’ character. If you do something, you have to give it everything. If you paint, paint as you will. The door can serve to enter and exit the house. But if you can't get out, you have to take down a wall. You have to have no misgivings. Isn’t this what art is all about?

Gillian Ayres is 87 this year, and her works still retain immense power. This shows not only that her art continues to provide an experience as profound as life itself but, more importantly, it proves that the history and life of abstract painting are not over. Whether or not abstract painting is meaningful is entirely dependent on the significance and perseverance of the people making it — of the art they make. With the CAFA exhibitions of Follow the Heart by Sean Scully, John McLean's Like Singing and Dancing, and now this exhibition of Gillian Ayres' work, our museum has drawn a singular line through British abstract art.

This series of exhibitions shows that abstract art is an expressive form in contemporary art, no less powerful than any other medium or form; and that it can take the spiritual temperature of the present moment. What matters is making abstract art, and making it properly and authentically. In these circumstances, it can embody the value and meaning of life.

Artists do not engage with abstract painting because they cannot paint reality, nor do they paint abstractions because they cannot paint good landscapes. This is not the case at all. Abstract painting represents human values; its longevity in history and across cultures depends on the strength and persistence of humanity’s living will, not the pursuit of trends and popularity. Abstract art at its best is rigorous, not a sequence of random marks.

We have three masters of abstract art: Scully, McLean and Ayres. It turns out that British contemporary art is multifaceted, and not to be reduced to a few names. This should provide significant encouragement to Chinese artists working in abstract art. We can truly study art history and engage with museums, we can discover true art, and we can overcome the blind spots that current fashions do not allow us to see, in order to show our understanding of art and our respect for people.

Prof. Wang Chunchen is head of the Department of Curatorial Research of CAFA Art Museum at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in China. He has translated over 10 books of art history and theory and curated many exhibitions including the Chinese Pavi¦ion at 2013 Venice Bienna¦e.