Titian, Assumption of the Virgin, 1515-1518, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Italy

Bridgeman Images

In 1979 I went to Venice: I was head of painting at Winchester Art School and we took the students to the Frari. I saw Titian’s Assumption — a painting about a woman rising up to Heaven. I suppose the first thing you notice about this painting is its subject matter, even if I don't think of painting in such terms. Painting is simply making marks — you see the marks and what they do. There is no need for stories in painting. The Assumption is meant to be extremely joyous and it is, even if its subject is religious and I am someone without any religion at all. We are living through a time where people quite like non–beautiful things. But I like beauty, absolutely. I like the idea that people can be knocked off their feet by looking at art or nature. Is tragic art necessarily stronger than joyous art?

Hokusai, Ukiyo-e Print of the Tama River and Mt. Fuji, 1823-1829, Private Collection

© Photo GraphicaArtis / Bridgeman Images

I don’t like perspective, I find it alien — and part of the gloriousness of the Hokusai is its use of space. It is perfectly possible to argue that the modernist sense of space has come from Asia. Van Gogh was profoundly attached to Japanese prints and had 350 of them. But I didn’t come to Hokusai through Van Gogh. When I first saw Hokusai’s works I just loved them. I simply respond to the shapes. But it is not as simple as that. Of course, I like some more than others. I have always noticed that Chinese paintings use white as a colour. Very much so, very often. It is possible that the French Impressionists took this from the paintings from Asia. We even get half of our gardens from China and Japan.

JMW Turner, Snow Storm - Steam-boat off a Harbour's Mouth, exhibited 1842

© Tate, London 2017

I don’t know how England produced such a wonderful painter; I had one on my bedroom wall when I was a teenager, aged about 13 or 14. I have a sense that the people who ran museums could not see the late paintings by Turner or Monet: they thought they were sketches half of the time. As I have said, I love the idea of an art in front of which you can lose your feet. Turner used to want to make sublime paintings and he meant it. He did this in his landscape paintings. Shock, sublime — these are paintings that want you to be exalted. Yes, exaltation is the right word.

Claude Monet, Nympheas, 1908

Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, 1981. 128

Monet’s sense of light is just glorious. Look at the nympheas paintings, or the haystack ones. The haystack is such a very ordinary shape and he painted them in different lights. Painting is about light, generally speaking. When I think of Turner and Monet I partly love them because they pushed painting beyond what had been seen before. I love the creativity of it, that it comes out of the medium. For me, that is vital.

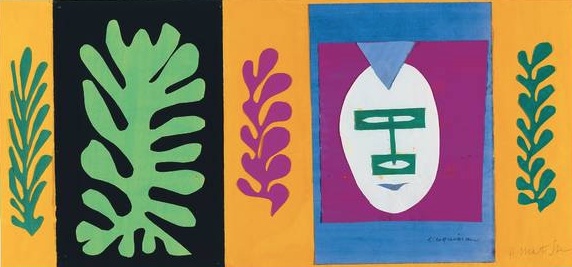

Henri Matisse, Eskimo, 1947

Designmuseum Denmark. PhotoPernille Klemp

© Succession H. Matisse/ DACS 2017

When I was a student, William Coldstream [a famous Euston Road School painter] said to us: “Matisse can pass us by”. I was probably 18 at that time, half way through being an art student. I said, in response to what Coldstream said about Matisse: “He can pass you by; he is not going to pass me by.” Everyone looked a little shocked that I had spoken out in this way. Matisse said he wanted his art to be like a comfortable armchair for the tired businessman to sit in; that you could relax and step into his art. My 1980s paintings are more turbulent than that, but I think we underestimate how much we learn from those things that are different from us, or even that we dislike. I know some people have said that my more recent paintings are Matisse–like. But if so, that’s an accident, I think.