In the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul — residence to Ottoman Sultans for almost 400 years — there is a passageway just outside the harem, a beautiful arcade that is unlike any other. It is called The Gathering Place of the Djinn. The ancients used to say that as you walk through this brightly–coloured passage you must stop your mind — stop thinking and questioning and judging, even if for a few precious minutes — and just watch, observe, take it all in, and allow yourself to be part of what you see and where you are. Every time I look at a painting by Gillian Ayres, I find myself zoomed into a similar passage in time.

Gillian Ayres’ art resembles a mansion that has its massive gates wide open to visitors from all backgrounds and all corners of the world. Perhaps what a Welsh or English visitor would see in her paintings would be different from what a Turkish or an Indian or a Chinese visitor would see in them. And that is quite all right. In fact, Ayres understands, and even encourages that kind of openness, multiplicity, fluidity. Her work refuses to be narrowed down to a single message or a single story. She is free, and as we stand looking at her paintings, allowing our feelings to take over our thoughts, so are we.

Where the Cymbals of Rhea Played (detail), 1986/1987, Oil on canvas, 224 x 210 cm

Throughout her long and prolific career, Ayres’ style altered significantly; it can be said that the painter went through various seasons of different duration and intensity. Her earlier works differ radically from her later works. Art is always a journey and every journey changes the person undertaking it.

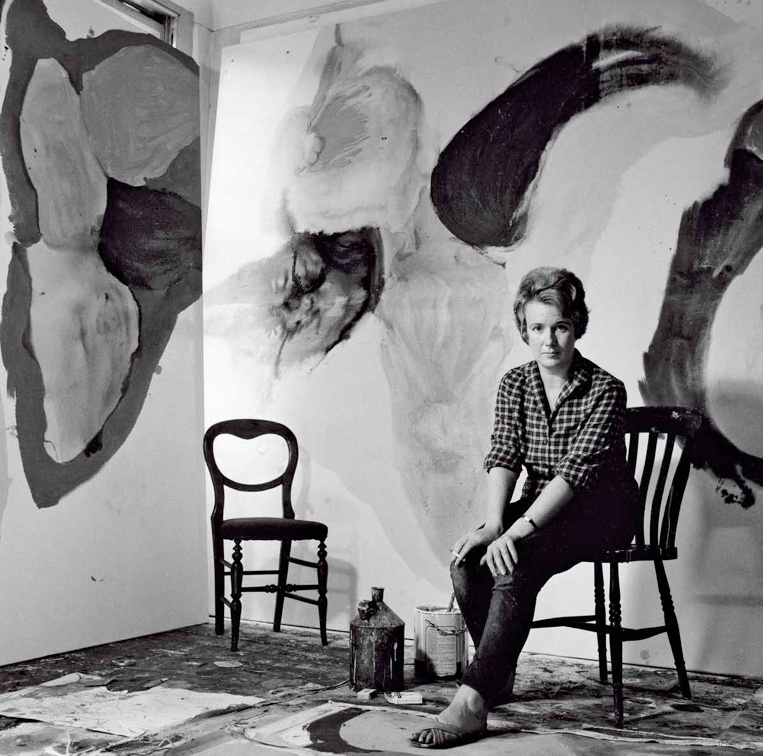

There is a black and white photograph of the artist on my desk as I am writing this piece. In the photo Ayres is in her studio, sitting on an old chair, splatters of paint by her feet. You can feel that this is the place where she spends most of her days, most of her life even, inhaling the sharp smells, touching and almost tasting the pigments of colour, this limited space with its unlimited possibilities. A room where infinity resides. Behind her there is a large painting, taller than the artist herself, and much bigger — a reminder that art is not only cerebral or emotional, it is also a very physical task. How long did it take her to complete this painting? In one of her interviews Ayres says that when she was younger she would do dangerous things, painting and working for hours while precariously balanced on top of a ladder, but as she got older she was not able to continue in the same reckless way. Was the passage of time the reason — or one of the reasons — why her paintings changed? She does not answer. There is no answer. Life is about change. Art is about change, and that is all we need to know.

Gillian Ayres, photographed by Jorge Lewinski, 1963

What intrigues me most about this particular photograph is the existence of a second chair right behind the krst one. It is empty. It is as if Ayres is inviting us, her visitors/viewers, to come and sit with her for a little while, and be part of that zone where she walks, day in and day out, the thinnest line between solitude and connectivity, sanity and insanity, silence and voices. The expression on the face of the artist is warm, welcoming and determined, but not necessarily encouraging. She wants us to join her in her studio, provided we do not ask her too many questions about the meaning of each and every one of her works, provided that we take it all in quietly, as though we were traversing The Gathering Place of the Djinn.

Altair is one of my absolute favourites. The dazzling star. Both within sight and quite afar. The brightest and the darkest and the happiest and the most melancholy of blues are present in there, side by side — coexisting, clashing, moving, dancing, breathing. I can look at this painting for hours, happily pulled towards its magnetic field. Shapes and spaces. Precision and ambiguity.

Altair, 1989-1990, Oil on canvas, Diptych, 224 x 427 cm

To other people this painting might mean different things. To me it is the blue that I encountered as a child in the house of my grandmother, the woman who raised me. My grandma was a healer, of sorts. A storyteller, as well. Her stories always began in the same way: “Once there was, once there wasn’t...” As soon as I heard this line, I knew I had to abandon linear logic and rigid reason. I knew that I was entering a magical country, a topsy–turvy world where time ran in circles. Whenever Grandma narrated a story, she would keep a blue stone nearby. A turquoise. Over time I came to see that particular colour as the key to Storyland. Then, I moved on and I forgot that stone, I forgot that blue — until I came across this wonderful painting by Gillian Ayres. Altair . There it was again. The key to the Land of Creativity.

Gillian Ayres is among the most important and fascinating abstract artists of our times. There is a restless energy and boundless courage in her work, but also a calm, accepting wisdom. Spirited yellows, mesmerising blues, wilful reds... Just like in my grandma’s stories, in Ayres’ paintings, colours have unforgettable personalities. They talk. They listen. They breathe.

East and West, it is rare to find an artist with such strong convictions who can let go of herself and become one with the universe. An artist who understands chaos and cosmos in equal degree. Discipline and spontaneity. An artist who at no stage in her life has lost her curiosity and sense of wonder. An artist who values freedom above everything else, and cannot possibly be conkned to boxes or categories of any kind. An artist who gently but krmly holds us by the hand, and helps us to connect with something other than our limited physical selves. “This is how you would see the world,” she seems to say, “if you could only see it through my eyes.” And the wonderful thing is, we can. When we get lost inside one of her paintings, we can see the world in a completely diuerent way. She introduces us to inknity: Gillian Ayres.

Elif Shafak is one of today’s most inuuential international authors and intellectuals. Her books have been published in 47 languages and she was made a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres by the French government in 2012. An advocate for women’s and LGBT rights, Shafak has pub¦ished 15 books, 10 of which are novels, including The Bastard of lstanbul and The Forty Rules of Love . She is the most widely read female writer in Turkey.