A white line bisects a space of intense blackness. Two curving lines – whose geometries differ slightly – sit in sublime misalignment balancing an all-consuming emptiness. (Fig.1) It is hard to believe that such simplicity of gesture and composition should command so much attention. The viewer is drawn in, and, as if standing on the edge of a great abyss, struggles against the vertiginous desire to fall into the deep blackness. The feeling is almost overwhelming... and then, there is the line. Delicately drawn it confidently reasserts itself, drawing attention once again to the surface and pushing the viewer back from the brink of nothingness.

There was something undifferentiated and yet complete,

That existed before heaven and earth.

Soundless and formless, it depends on nothing and does not change.

Tao-te Ching Chapter 25,4thC BC

Fig.1 Jiangnan H2, 2015, Acrylic, ink and charcoal on canvas, 120 x 180 cm

Fig.1 Jiangnan H2, 2015, Acrylic, ink and charcoal on canvas, 120 x 180 cm

The blackness persists nonetheless as does the unconscious desire to allow oneself to be consumed by the dark heart of what lies beneath. So begins the universal struggle between the void and the non-void made manifest in just one of several intense paintings by the artist Wang Jian.

Nothingness was not, the existent was not;

Darkness was hidden by darkness…

There was neither death nor immortality then;

No distinguishing sign of night nor of day;

That which became was enveloped by the Void

Rigveda 10.129 (Abridged, Tr: Kramer / Christian) 1500-2000BC

Said to be the foundation of Hinduism, this extract from a much longer text, known as the Hymn of Non-Eternity pre-dates all Western philosophies, Taoism and Buddhism, as well as the birth of science and logic – yet, to date, it is has only been partially translated. The language in which it is written, an ancient form of Sanskrit, is obscure and often unintelligible. Many believe that all forms of language are by their very nature problematic: gendered, (ill-)defined, fixed and often found failing when trying to articulate the unspeakable or impossible. Many theorists and philosophers have commented that regardless of the language, no matter how poetic and/or descriptive, whether spoken or written, words are unable to successfully (or even adequately) articulate a metaphysical conundrum such as the Void. Ludvig Wittgenstein, the Austrian-British philosopher, was very much aware of the inadequacies of language and in his 1921 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus posited “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”. Perhaps this is why art exists. As a visual language it can ‘speak’ directly to the mind, the heart and the soul of the viewer.

On encountering Wang Jian's work for the first time one is immediately struck by the scale, confidence, absolute ease and the endless (and multiple) challenges his paintings present. Accepting Wittgenstein’s statement one of the biggest obstacles therefore in writing about Wang Jian’s practice is defining how best to interpret and articulate his work in the form of a text – how can mere words reflect and express such universal themes? To succeed one must approach Wang Jian’s work through a series of opposites, binaries, dichotomies and contradictions. His work can only be written about from the perspective of what is and what is not.

The postmodern would be that which, in the modern, puts forward the unpresentable in presentation itself; that which denies itself the solace of good forms, the consensus of a taste which would make it possible to share collectively the nostalgia for the unattainable; that which searches for new presentations, not in order to enjoy them but in order to impart a stronger sense of the unpresentable.

Jean-François Lyotard, “Presenting the unpresentable: The sublime” in Artforum, 3, 1982.

Renée van de Vall, currently Chair of the Department of Literature & Art and head of the faculty research programme in Arts, Media & Culture at Maastrich University in the Netherlands suggests that the sublime as defined by the French philosopher, sociologist and literary theorist Jean-Francois Lyotard’s “presents itself with a silence experienced within the gaps of comprehension.”[1] What is important therefore in ‘looking’ at the silences in the work of Wang Jian is to listen. The sound of, or sounds within, his works are profoundly ‘unpresentable’, yet he strives to make it/them present nonetheless. The silence he creates is the sort of silence that creeps into one’s consciousness when waking from a deep sleep. An absolute, almost deafening, quiet.

While his work is silent it also seems to hum, or at the very least oscillate or vibrate. Large, bold canvases of vision-sapping blackness, broken only by the most sensitive and beautifully articulated lines,[2] force the viewer into witnessing the continual unrest between the surface and the abyss that lies within each work. This polarity establishes a natural rhythm, something akin to the resonances of the Indian sacred sound ‘om’ when chanted as part of a mantra or perhaps the sound-vibrations that occur between sub-atomic particles – a scientific comparison that blends the physical, the metaphysical and the spiritual much as Wang Jian does himself.

Wang Jian’s works could be considered as visual autobiographies. Everything and nothing are equally important to him and to his work. Every thought and feeling, his time in the studio and every other moment of his life, is compressed and held in the vast emptiness of his black canvases as well as in the small blank spaces he sometimes leaves unpainted. This process is critical and the outcome sometimes unclear until the very last moment. Thus to some extent Wang Jian’s work could be defined in terms of Chinese Maximalism – a term derived from literary critical theory and re-worked by the art critic, historian and curator Gao Minglu to describe a type of art that emphasizes:

…the spiritual experience of the artist in the process of creation as a self-contemplation outside and beyond the artwork itself... These artists pay more attention to the process of creation and the uncertainty of meaning and instability in a work. Meaning is not reflected directly in a work because they believe that what is in the artist's mind at the moment of creation may not necessarily appear in his work.

Kristin E.M. Riemer Chinese Maximalism debuts, UB Reporter 9 October, 2003

In complete contradiction to this (perhaps too easy) definition, it also becomes apparent from looking at Wang Jian’s work that ‘nothingness’ is also a very important aspect of his practice. Ancient Eastern doctrines have battled with notions of ‘nothingness’ for millennia – the Rig-Vedic hymn referenced at the beginning of this text is 4,000 years old and seeks to explore the concept. It leads to an interesting contradiction: while Eastern philosophies consider ‘nothingness’, or the Void, to be a place of extraordinary tranquillity, nirvana, bliss, eternal potentialities, ending, birth and rebirth (thus something to be embraced), Western philosophers, have always seen the Void as a terrifying concept. For centuries in the West, it was thought that a void could not exist and must be filled with some ‘thing’ often referred to as chaos, sometimes manifested as a deity or the (trans-faith) ‘one God’. Wang Jian’s sensitivity to these philosophical contradictions no doubt developed as a result of his early self-directed studies when he read extensively on Eastern and Western literature, art, history and Zen. Capturing and making manifest the abyss, ‘nothingness’ or the Void in the form of a work of art is the challenge that Lyotard described as leading to the postmodern and one that Wang Jian presents himself.

Wang Jian’s ideas are fixed, complete and finished – to some extent in an instant as his practice often has a starting point in photography – and then fixed again in the pragmatic form of a painting. Yet almost all of his works are simultaneously in a state of continual flux and uncertainty. To paraphrase the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Zi: ‘there [is] something undifferentiated and yet complete’ in each work. So while Wang Jian’s canvases are accomplished and whole they are also unfinished. Many of his paintings carry a recurring motif – a small section, often the angle created by the intersection of two lines – that is left unpainted: a white ‘nothingness’ in a dark, broad and all-encompassing Void. (Fig.2)

Fig.2 Jiangnan H6, 2015, Acrylic, ink and charcoal on canvas, 120 x 180 cm

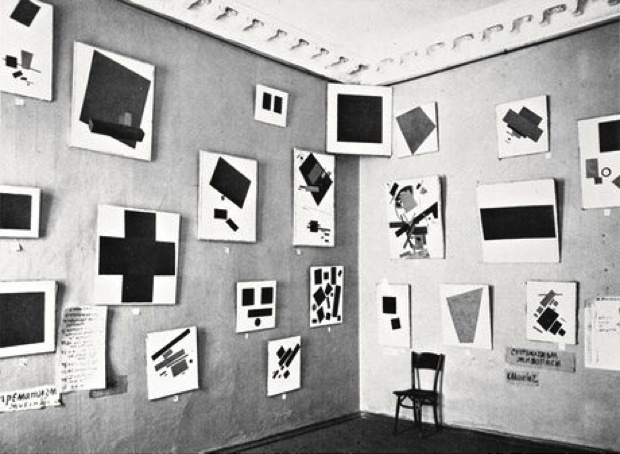

Colour, or the lack thereof, is important in Wang Jian’s work. The greatest Chinese masters believed that colour deadened or excited the senses and therefore it was thought not appropriate in the search for purity in artistic works. The majority of Wang Jian’s works are, therefore, appropriately monochromatic. In discussing these hyper-minimalist works one cannot avoid referencing the Russian painter and theorist Kazimir Malevich. A Christian mystic Malevich believed that art was intended to convey a sense of the spiritual. In attempting to reach that position, a point he is often paraphrased as saying would be the ‘zero point of painting’, he sought to strip away from his work all superfluous and/or decorative elements. This led to his 1915 Suprematist Manifesto and the exhibition of his first (all) black and first (all) white paintings in the same year. (Fig.3) In reaching that point Malevich set in train a series of responses, perhaps more aptly referred to as reflex actions, that led to both Abstract Expressionism and Colour Field Painting.

Fig.3 installation view 0,10 The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting, Petrograd (now St Petersburg), Russia 1915-1916, Russian State Archives

Each of these styles of painting has some synchronicity with Wang Jian’s practice. American colour field painters such as Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still often created vast monochromatic, or at most trichromatic paintings, that were intended to be on such a scale that the viewer, standing in front of a work, would have their entire field of vision filled with the painting. The ‘real’ world of the museum or gallery would be lost and there would be only the object (artwork) and the viewer. All three artists engaged with the emotional, mythical or religious that echo the minimalist paradigms established by Malevich. The scale of many of Wang Jian’s works lead the viewer in the same direction – as described in the opening paragraphs of this text – the point where one becomes lost, subsumed in his work. With Abstract Expressionism, the emphasis is/was much more focused on the spontaneous, automatic or subconscious. The artist was seen almost as a vessel or channel for the act of creation (the making of art) – a combination of emotional intensity and self-denial that similarly makes an appearance in Wang Jian’s paintings.

Discourse on the personal, intimate or spiritual in art and art-making has been anathema to many art critics for decades. It has certainly been out of fashion to write about such things with many key publications choosing not to review or comment instead focusing on other aspects of an artist’s work. However, over the last decade or so there has been a resurgence of interest in the spiritual by many very established international artists whose work has moved toward the sublime (after Lyotard) and the transcendent – these artists creating works as a response to the all-consuming force of nihilistic postmodernism, neoliberalism and globalisation.

In the post-internet age physicality and spatiality (being and feeling in the real world) are ever more important as a reaction to the ubiquity of the electronic image and the mediated or false dimensionality that current technology limits us to. Abstract art still demands to be looked at (actually) and experienced (directly) and thus is ever more valuable as a response to the all-encompassing and irresistible draw of the web/digital. In the face of all of this many artists are returning to fundamentals in an attempt to remind themselves, and us through their work, that we are all human: thinking, breathing, biological, natural, alive and current and that there is something ‘other’ out there, something intangible and beyond our comprehension. The American artist Bill Viola, in his essay Reasons for knocking at an empty house, 1995 described his feeling on the matter “The crisis today in the industrialized world is a crisis of the inner life, not of the outer world.”[3] Ironically, it is when looking at the outer world that Wang Jian’s work even more forcefully directs the viewer into an appreciation and understanding of that which is intangible.

Fig.4 Jiangnan S1, 2015, Giclée print, 22.5 x 30 cm

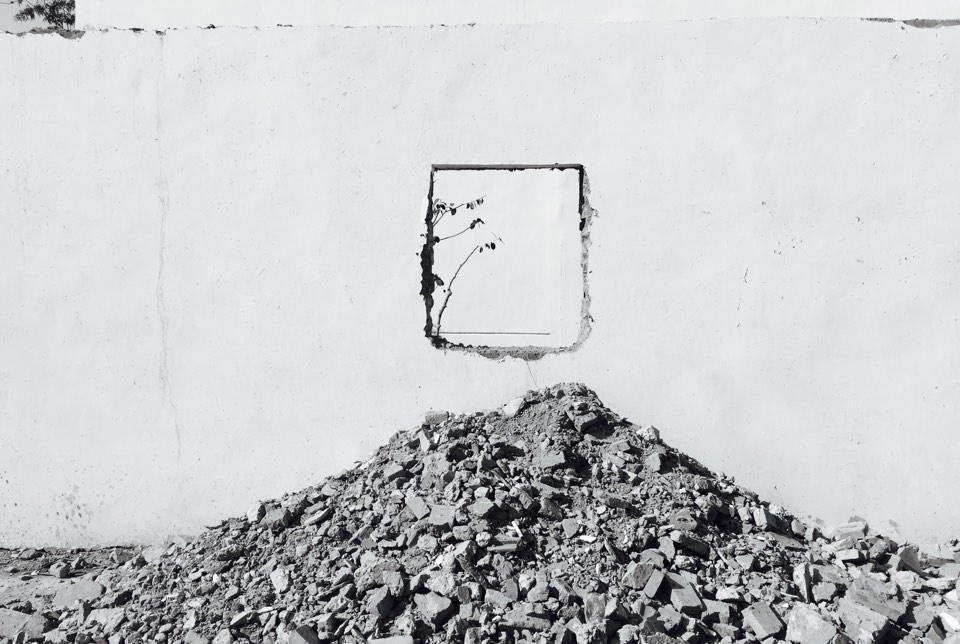

Most of Wang Jian’s photographic works are of mid-scale and make for a striking contrast to the ambitious dimensions of many of his oil paintings. This does not however, imply that the photographs are less important. On the contrary, many of his photographic ‘sketches’ act as departure points for his other works, although it is hard, almost impossible, to identify any literal translations. A loop of metal rope coiled across the rectilinear intersections of paving slabs suggest to Wang Jian how a line and a curve in a painting might touch. (Fig.4) He speaks of the (intimate) relationship that occurs at that moment and at that point of contact ‘it could be a kiss or a conflict’.[4] Yet the photograph itself focuses the viewer on the details of the physical environment, the tones and textures and the extraordinary chance meeting of two materials/objects that in turn creates a minimal, but no less beautiful, composition. Stark contrasts – the way a shaft of light falls into a rough architectural space – blur the boundaries between foreground, object and background. Spaces, places and lines populate his photographs… but the overriding sense is one of emptiness, absence or erasure. Apertures in walls (Fig.5) and dark doorways (Fig.6) suggest an unknown place beyond and, in one or two works tectonic surfaces collide and fracture. Broken plaster on walls (Fig.7), cracked limestone rock (Fig.8) (on the Jurassic coastline of Croatia) photographed in intense close-up focus the viewer’s eye on the fissures or spaces in-between. (Fig.9) In Celtic mythology the ‘in-between’ are places of transition, neither one thing nor the other, places of power, where the extraordinary is possible and where the bonds of reality and the everyday are shed. A universal archetype these myths appear in different forms in many different religions including Taoism and Buddhism. The liminal, the fissures and areas of intense blackness in his paintings all gesture at ‘nothingness’ and bring us full circle resolving Wang Jian’s practice once again into a coherent body of work that is at once spiritual and sublime, relevant and provocative.

Fig.5 Jinze S2, 2016, Giclée print, 30 x 22.5 cm

Fig.6 Jinze S1, 2016, Giclée print, 22.5 x 30 cm

Fig.7 Jinze S6, 2016, Giclée print, 4.27 x 8 cm

Fig.8 Croatia, 2016, Giclée print, 4.27 x 8 cm

Fig.9 Ruicheng S1, 2016, Giclée print, 4.27 x 8 cm

‘Nothingness’, or the Void, is not an intellectual puzzle, it is a sensory perception – it must be felt to be understood. Don't struggle too much to comprehend and interpret Wang Jian’s work. Don't stand in front of his paintings and try to recall pages of Eastern and Western art history and philosophy that might apply. Don’t try to translate his photographs into his oil paintings nor seek to construct any narratives. Simply feel. Let yourself be with the work. Wang Jian makes art that must be experienced. Place yourself squarely in front of it and let go.

25 Sept 2016

[1] Renée van de Vall “Silent Visions: Lyotard on the sublime.” Art & Design Profile No. 40, 1995

[2] The Tang dynasty poet, musician, painter and statesman Wang Wei often set his apprentices the task of recreating an immense body of ‘emptiness’ by means of just a slim brush. (Francois Cheng (trans: Michael Kohn) Empty and Full: Language of Chinese Painting, Shambhala Publications Inc., 1994)

[3] Bill Viola Writings 1973–1994 MIT Press, Cambridge, USA, 1995

[4] Wang Jian to the author WeChat text exchange, trans: Frankie Lu, September 2016