Once Upon a Time

by Bao Dong

According to T.J. Clark, the 20th century was marked by only two significant events: modernism and socialism. These two events were interdependent, each attempting to establish a new world order: one based on the rectilinear plane of the canvas and new sensibilities, and the other founded on the principle of complete equality within a new system. Yet, these two ideologies also repelled each other. Ultimately, different nations and regions seemed to align with either one or the other. In the advanced capitalist countries, modernism continued as a reflexive form of modernity. Conversely, in less developed nations such as early 20th-century Russia and China, socialism emerged as the chosen path, notably embracing realism/naturalism as the legitimizing artistic notion underpinning their overall social revolution.

These are all matters of the past. However, what we cannot avoid acknowledging is that we still reside within the aftermath of that brief 20th century, spanning from 1919 to 1989. Regardless of whether we term this era "contemporary" or "postmodern," the concepts of revolution and historical coordinates persist, particularly in this era of resurgence. In China, discussions on art cannot be disassociated from this context. The artistic ideology of socialist realism and the painting language of the Soviet art based on it, along with the resulting nationalistic style, once nearly encapsulated all academic painting. This formed the thematic relationship in artistic creation during that period. Starting from the 1980s, as personal narratives gradually replaced revolutionary narratives, the "revolutionary" language of the Soviet art in painting was used to portray the immediate life of individuals. Throughout this process, it underwent transformation and alteration, evolving into "life stream" and "close distance." In this sense, the trajectory of Chinese painting in the 20th century can be summarized as a historical construction and dissolution of realism/naturalism. Subsequently, it grew into artistic practices stemming from this legacy and the direct importation of artistic notions, comprising what we observe in contemporary art today.

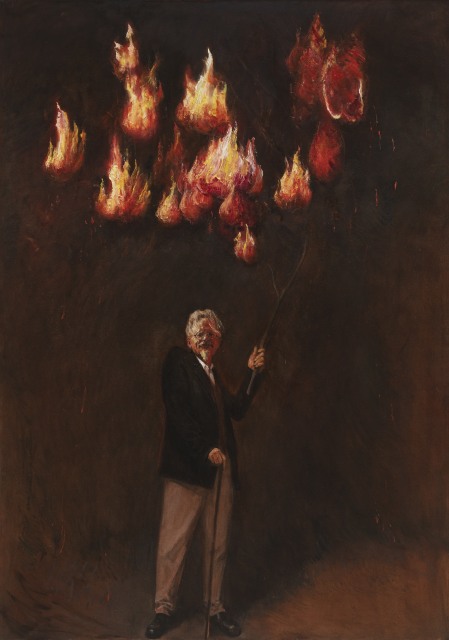

Therefore, at this juncture, Qi Xing's thematic grouping of Trotsky in his paintings appears to intentionally create distance from the present time. This contrary move aims to delve deeper into our already impoverished historical understanding. It's not that Qi Xing is conducting a revisionist exercise in historical research but rather emphasizing how, compared to figures like Trotsky, deeply involved in the history of art as idealistic or radical revolutionary practitioners, the criticisms, actions, and societal involvement proclaimed by contemporary art today seem vain and feeble. Not to mention various forms of opportunism.

However, Qi Xing did not adopt the method of Socialist Realism in creating these works—indeed, Trotsky himself did not endorse such instrumentalized art. His artistic judgment can be gleaned from the list of artists he associated with: Brueghel, Rivera, and Frida—indicating a montage technique and symbolism rather than a tool-based artistic approach used by Qi Xing to "edit" Trotsky's image and fragments of memory, much resembling the symbolic montage of early Soviet avant-garde film (such as Eisenstein). While Qi Xing paints the past, it is more of a reverie. In this sense, these works can be seen as a series of conceptual drawings for a film because they not only reproduce a scene or moment but also express ideas, brimming with readability. In terms of painting language, Qi Xing did not adopt the Soviet art style but rather employed an even earlier technique, using a classical oil painting method: an earth-red base, transparent yet thin shadow areas, limited use of blue. This simplified color spectrum drives a restrained painting temperament, reflected in the shaping and brushwork, carrying an honesty akin to the roughness of a certain circulatory painting school, devoid of the greasiness often found in contemporary academic realism.

The seemingly concluded history has not actually become a thing of the past. Often, the past re-emerges suddenly, much like this exhibition, reminding us of a fact: the invisible or overlooked facets constitute the decisive parts, akin to the dark matter within the universe.

November, 2023

Qi Xing, 1982, born in Tangshan, Hebei province. Graduated from Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2005.

Bao Dong, born in Anhui in 1979, graduated from the Art History Department of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in 2006. He is an active art critic and curator of the new generation in China, co-founder and artistic director of Beijing Contemporary Art Fair.