Philip Dodd

“It’s not so simple” — this is Gilliian Ayres’ frequent and robust response to interviewers who propose an explanation for what the artist has done; or who want to know why she has made the marks that she has.

It may be that “It’s not so simple” is no more than a way in which the artist guards the meaning of what she does — perhaps from herself as well as others. If this is the case, then the interviewer might quote the French critic Roland Barthes in The Death of the Author (1967), that “writers are just the first readers” (or “artists are just the first viewers”), and blithely move beyond what the artist says. As the English novelist DH Lawrence said in Studies in Classic American Literature(1923): “Trust the tale, not the teller.”

But what if Gillian Ayres’ declaration, “It’s not so simple”, offers a route into understanding her career and art?

“I did actually think, if you are going to get out of the city [London], go somewhere very wild, not like the Home Counties [the counties surrounding London]” 1

In the most obvious and simple biographical sense, Gillian Ayres is English — born in 1930 in a suburb of London and educated at one of the most prestigious schools in England, St Paul’s School for Girls. She went on to art school in London, Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts, which she entered at the unusually young age of 16 and left without sitting any exam. She has always been a rebel with a cause.

But what would it mean to call Gillian Ayres an English painter? That is when things become far from simple. Gillian Ayres belongs to that generation of artists who lived through the Second World War and went to art school in its aftermath. Her teachers included key figures in the Euston Road School of painters, who were “realist”, tonal painters, their chosen colours often muddy, the scale of their paintings small. In that sense Gillian Ayres is not an English painter — nor did she follow in any substantial way in the footsteps of the abstract painters associated with the St Ives School, whose abstractions were mostly modestly sized, landscape influenced paintings.” 2

Many critics argue that the abstract artists of her generation, including Gillian Ayres herself, are indebted to American Abstract Expressionism, which was first shown in Britain in the Tate in 1956 — an exhibition that undoubtedly was the spur to the 1960 exhibition Situation , in which Gillian Ayres and other British abstract artists showed huge works.

“The whole idea of the canvas as an arena in which to act, an area and what one does with it. Pollock working on the ground: I wanted to find out about that, obsessively. I did find it tremendously exciting.’’ 3

As can be seen from this comment, Ayres herself has recognised the power of the American example. Even in her 1980s paintings there are still signs of the excitement of painting–as–performance — in the way paintings such as Where the Cymbals of Rhea Played (1986/1987) include a frame within the painting (or is it a proscenium arch?) within which the action takes place.

But the example that Pollock gave Gillian Ayres is just a small part of any account of her work — an explanation of her work is not that simple. Look at White Wind (1997), which at first glance looks like an airborne landscape, and it is possible to see what Ayres herself is happy to acknowledge: her indebtedness to the way Chinese artists use white, and the indiuerence of Asian artists to perspective.

Whatever else the globalisation of art has done, it has allowed us to unravel the notion — prevalent in art criticism in the middle of the last century — that the rest of the artworld followed the American road. Gao Minglu, the distinguished art critic and curator, has argued that contemporary Chinese abstract art is a mixture of abstract language, traditional Chinese art language and Chan Buddhist practice and ideas.4 It is equally the case that, even though American abstract artists such as Robert Motherwell and Mark Tobey accom– modated elements from Asian cultures — whether in the use of ink or Zen ideas of nothingness — in doing so they did not become Asian artists, any more than Gillian Ayres does.

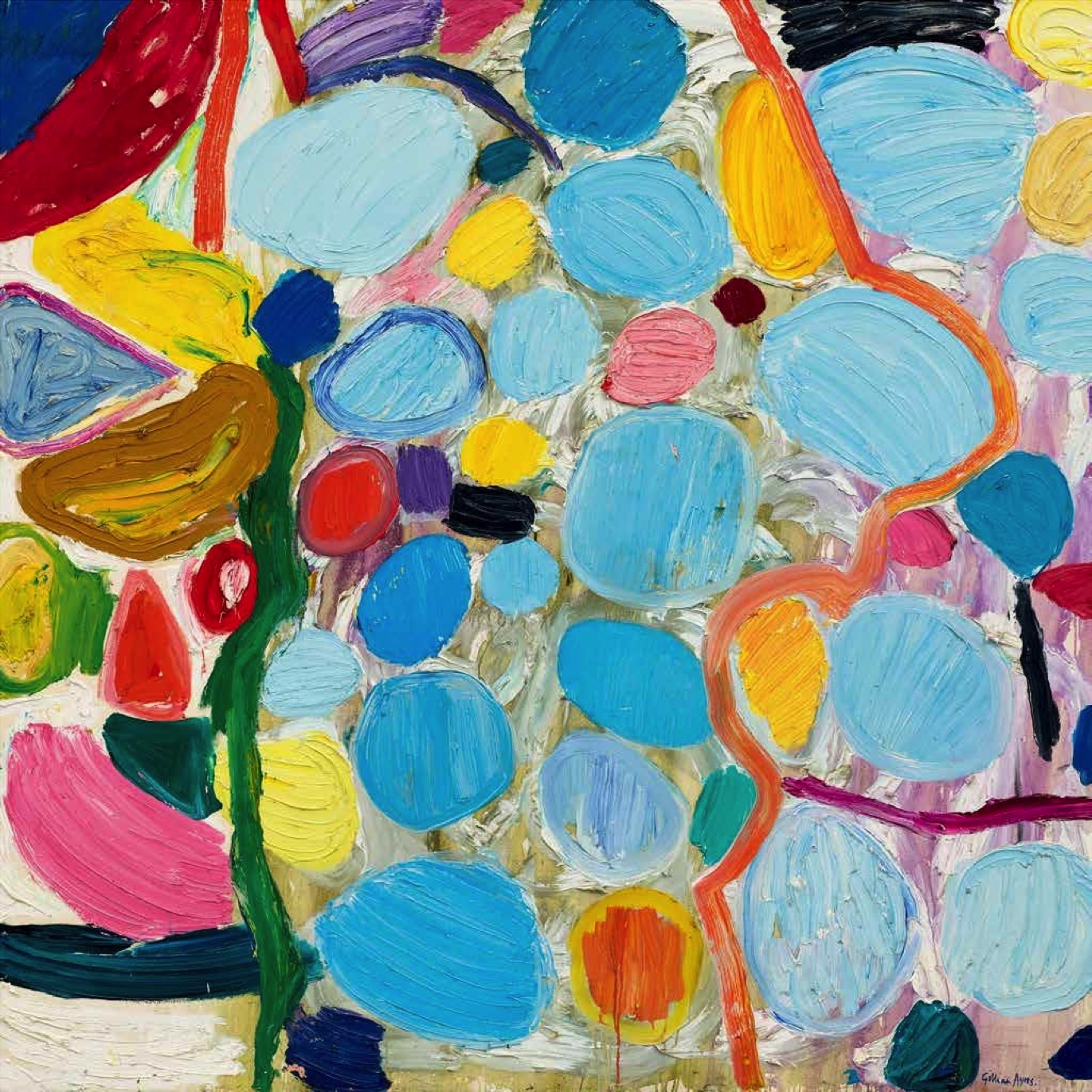

Furrina, 1994, Oil on canvas, 182.8 x 182.8 cm

In this spirit, perhaps it does make sense to interrogate Gillian Ayres as an English abstract artist, one who draws on long – standing “local” traditions, as well as more global ones. Many critics have made a connection between her art and nature. The English critic Tim Hilton described the way “light finds its way in and out of the small valleys and crags of the impasto”5 in some of Gillian Ayres’ “thick” paintings of the late 1970s and early 1980s, arguing that when looking at the work, “It is necessary to invoke nature”. There is no doubt that particular places — especially wild ones — have been important to her, and her studio in the south west of England gives direct access to a garden that she has cultivated herself, although in conversation she is quick to point out that many of the plants are from Asia.

“In a mad sort of way I saw nature like paint; and probably so did Turner”6

But nature and Gillian Ayres’ art have a far from simple relationship, as is evident in her above comment. The phrasing is interesting — not paint like nature, but nature like paint — as if paint precedes nature. Paint is as vital and alive and as various as nature itself. Look at the range of marks and the orchestration of colours in the 1979 Phosphor.

Phosphor, 1979-1980, Oil on canvas, 152 x 152.5 cm

Now it is the case that the historical connections between art and nature have been longstanding and complex, not least in England. One of the great gardens in England, Stourhead, was inspired by paintings by the French artist Poussin, which the owner had seen on a visit to France. Again, paint before nature. And the writer Oscar Wilde once famously said, in The Decay of Lying , that’ the sky is just a very second–rate Turner.' Art before nature, for a third time.

But Ayres’ nature and art are as far from the ordered nature of Stourhead as they are from the artful wit of Oscar Wilde. “Sublime” is a word that Gillian Ayres has often reached for when she describes both her own work and that of other artists she reveres — a word that has often been used to define the art of Turner. The word has a long history in European thought but its meaning crystallises in the 18th century, when the sublime as an aesthetic quality in nature is distinguished from the beautiful — the sublime is attached to turbulent nature, to objects and experiences that cannot be understood, generating feelings of being overwhelmed.

It is easy to see how Gillian Ayres’ paintings, particularly those of the 1980s and early 1990s, seem to reach for the sublime, with their overwhelming scale and size and their long, thick brushstrokes — the choreography of the marks in these paintings has the intensity of nature or life itself. As she told me in one of our conversations: “I like the idea of art that knocks you off your feet... artists like Turner wanted the sublime and used landscape. They meant it to shock.” But it is not so simple.

“Titian’s cherubs seem to invade our space — these invariably non–gravitational paintings, where forms move up to heaven and out of the canvas... Glazes are used to create an iridescent lustre to combine with the erotic sublime.” 7 Gillian Ayres, 1981 lecture.

In 1979, Gillian Ayres visited Venice and encountered the great Venetian painting of Tintoretto and Titian. Her idea of the erotic sublime is at first startling, but on reflection not so, when one remembers that Gillian lived through the years of the women’s movement, and that she was a close friend of the novelist Angela Carter, whose book The Sadeian Woman, a meditation on power and eroticism, was published in 1978. It is also the case that in the 1980s she began to name her paintings after goddesses (Furrina and Where the Cymbals of Rhea Played are examples in the Beijing exhibition of such naming).

“Erotic sublime” sounds like an oxymoron — after all, sublime conjures up the search for the ineffable and erotic refers to the body. Yet Gillian’s paintings of the late 1970s and 1980s might well be described as paintings of the erotic sublime. Here, nature is not observed, nor, as in much Western art, is a woman’s body the equivalent of nature. Rather, these paintings enact the experience of a woman’s body as it encounters paint–as–nature.8 They are exhilaratingly carnal. Perhaps it is for this reason that the paintings are the size of her body at full stretch, and that in this period she put paint directly on the canvas with her hands, making them profoundly tactile experiences.

The English philosopher RG Collingwood argued in The Principles of Art that Cezanne painted as if he were a blind man, and that the paintings were to be experienced as much through imaginative touching as by looking. The same is defiantly true of the extraordinary performative paintings of Gillian Ayres in the 1980s, some of which are turbulent, some ecstatic and some troubling. There is much talk now of “body art” and of performance — and these are too often seen as somehow an alternative to painting. But these paintings of Gillian Ayres are defiantly and definitively paintings of and by the body (as well as being alert to art history, both West and East). Her ambition is, as the artist herself has said, to make paintings that are “a complete combination of heart and mind”.

Is it any wonder that Gillian Ayres says, “It’s not so simple”? It certainly is not.

Philip Dodd most recently curated a major retrospective of Sean Scully in five museums across China. He has written numerous books on art, film and literature, and he has been named one of the “100 art innovators” by the US magazine Art + Auction (2016).

1 Quoted, Mel Gooding, Gillian Ayres (London; Lund Humphries, 2001), p120

2 Questions around the English– ness of English art have been intense for some time now, see Philip Dodd, 'Art, History and Englishness: An Open Letter from Philip Dodd', Modern Painters ,vol,1, no,4, Winter 1988/9, p40–41.

3 Gillian Ayres , with a foreword by Andrew Marr,texts by Martin Gayford and David Cleaton– Roberts, Art/Books, 2017, p41.

4 Gao Minglu,’Traditions and Contemporary Abstract Art in China', In Where Does It Ait Begin? Contemporary Abstract Art in Asia and the West (Pearl Lam Galleries: China, 2014), p10.

5 Timothy Hilton, Introduction, GHIian Ayres: Paintings, Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 1981 catalogue, p10.

6 Gillian Ayres , with a foreword by Andrew Marr, texts by Martin Gayford and David Cleaton– Roberts, Art/Books, 2017, p60

7 Lecture by Gillian Ayres, 1981, quoted in Gayford, p132

8 For a not unrelated argument see Robert Hobbs, ’Krasner, Mitchell, Frankenthaler:Nature as Metonyn' in Women of Abstract Expres– sionism (New Haven and London: Denver Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2016), pp 58–67. I should stress, though, that what sharply distinguishes GilIian Ayres' work is the conjunc– tion of the erotic and the sublime.